Indigenous Connections & Collections

Welcome to the inaugural blog of Indigenous Connections and Collections! This blog aspires to connect readers to Indigenous resources, information, and fun stuff at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center (IPCC) and online. Each month, new content will be shared on various topics.

November is National American Indian Heritage Month. The history of American Indian Day started in the early 1910s in “an effort to have a day of recognition for the significant contributions the first Americans made to the establishment and growth of the U.S.” On August 3, 1990, President George H. W. Bush signed a joint congressional resolution designating the month of November “National American Indian Heritage Month.”

As Indigenous* people, we celebrate, recognize, and honor our history and contemporary accomplishments every day. Learning about the 574 federally recognized and 63 state recognized Nations should be done year-round — not just in November or around Thanksgiving. It is important for Indigenous people to see the acknowledgement of their history in school curriculum, coverage of issues in the national media, contemporary accomplishments, and accurate portrayals in movies, television, and books.

*The term Indigenous is used broadly to include those labeled Native American, American Indian, Alaska Native, Hawaiian, First Nations, Aboriginal, and others like the Sami (Finland) and Ainu (Japan). Native American and American Indian are used interchangeably in this blog.

Monthly Feature

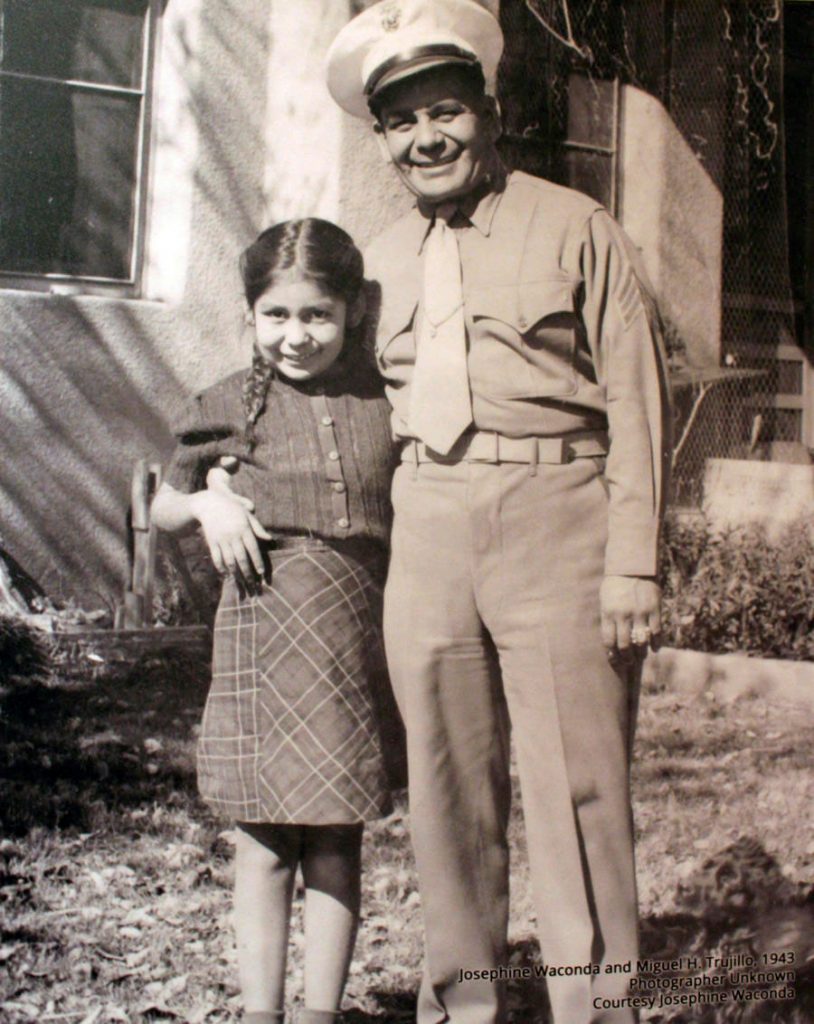

Despite a high percentage of Native Americans – women included – that served in World War I and II, they were not allowed to vote in the country for which they had served. New Mexico was one of several states where “Indians not taxed” could not vote because Native people living on reservations did not pay property taxes. Miguel Trujillo, Sr. (Isleta Pueblo) filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court, which argued that although he did not pay property tax on pueblo land, he paid federal income tax, and gasoline and sales taxes. A three-judge panel in Santa Fe ruled in Trujillo’s favor finding that the NM constitution violated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. On August 3, 1948, Trujillo, a World War II Marine sergeant, won Native Americans the right to vote in New Mexico.

Joy Harjo, Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is the 23rd United States Poet Laureate (2019-20), the first Native American to hold this post. An internationally renowned musician, poet, playwright, and writer, she has authored nine books of poetry, several plays and children’s books, and a memoir. She holds numerous honors, is chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, and is a founding board member of the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation. She is the invited author for the IPCC Pueblo Book Club on Tuesday, November 24, 2020, where she will discuss her current book, An American Sunrise. “This poetic narrative exemplifies of how the Muskogee peoples keep relevant their culture, core values, social constructs, and inter-connectedness with their world.”

Teaching Resources

Native Knowledge 360° Education Initiative from the National Museum of the American Indian. Here are Instructional Resources on various topics focused toward specific grades and subjects. Each lesson identifies which Native Nation(s) the lesson refers to, including region areas, Essential Understandings gained, and Academic Standards. The website provides a range of videos, teaching posters, exhibit guides, webinars, and links to websites.

Indigenous Wisdom Curriculum This project was created to provide New Mexico K-12 educators with unit plans to serve as a counter-narrative to the NM history currently presented to students. Centered on Pueblo core values and Pueblo-centered cultural perspectives, the curriculum aligns with NM State and Common Core Standards. This Pueblo authored curricula in Language Arts, Mathematics, and Social Studies is valuable to students from diverse backgrounds to foster understanding and respect.

Veteran’s Day

There are more than 31,000 Native Americans, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians that currently serve on active duty in all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces. More than 140,000 veterans identify as Indigenous. American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) males 17-24 years of age and AIAN women serve in the Armed Forces at a higher rate than any other ethnic group. Nearly half of all AIAN served in the Navy. Over 36% of AIAN veterans served during the Vietnam Era. New Mexico ranks fourth for AIAN veteran population by state.

Veteran’s History Project. In 2000, the United States Congress started the Veteran’s History Project at the American Folklife Center. The Project collects, preserves, and makes accessible the first-hand accounts of American war veterans from World War I to the Iraq War. This link takes you to the American Indian and Alaskan Native collection where you can browse digitized narratives. If you are a Native veteran and are willing to be recorded, consider adding your narrative to the collection.

On Veterans Day, November 11, 2020, join the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center for a video commemoration of Veteran’s Day with a presentation of colors, a flute performance, and blessing. The National Museum of the American Indian will also have a virtual program “honoring the service and sacrifice of Native veterans and their families and marking the completion of the National Native American Veterans Memorial.”

Fun Stuff

Using humor to express the realities of Native life and history, Ricardo Caté (Kewa) created Without Reservations, the only mainstream Native American cartoon that runs daily in the Santa Fe New Mexican newspaper. Once a social studies teacher, Caté commemorates important dates in Native American history. Read about his Art Through Struggle Gallery exhibit that was shown at the IPCC in 2018.

Super Indian Coloring Book, Let’s PowWow! Story and art by Arigon Starr (Kickapoo). Arigon is a singer, actor, playwright and comic book artist. You can find two issues of “Super Indian” on her website. Take a look at Arigon’s Portfolio here. The portfolio includes a Santa Fe Indian Market award winning image of Pueblo superheroes from an upcoming issue of the Super Indian series, plus pages from “Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers” anthology.

About the Author

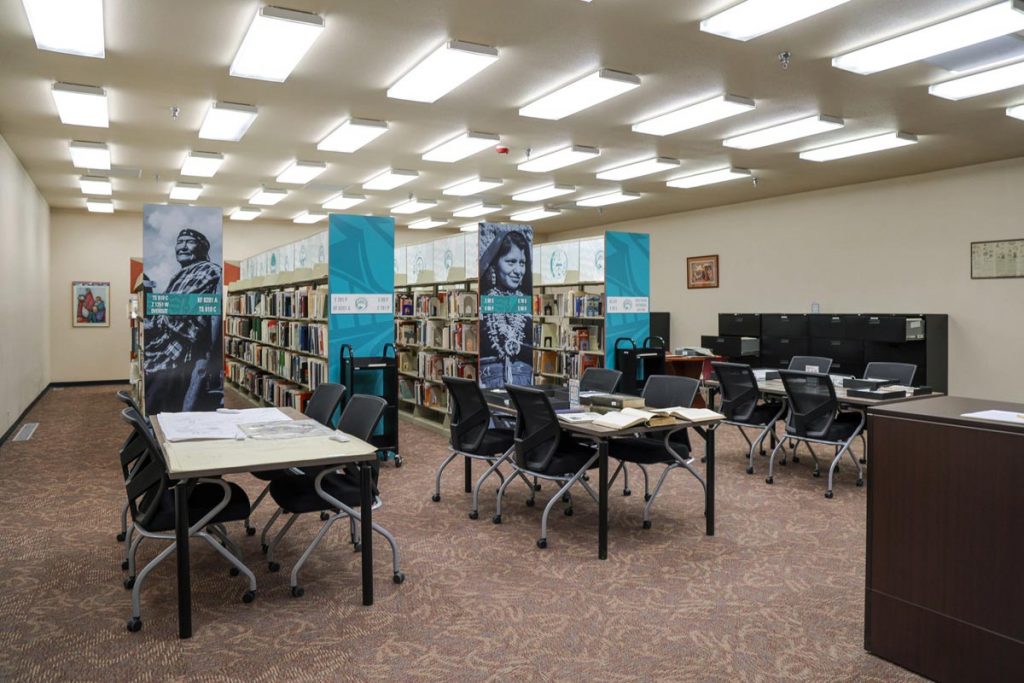

Jonna C. Paden, Librarian and Archivist at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center (IPCC) Library and Archives, is a tribally enrolled member of Acoma Pueblo. She grew up on the Laguna reservation with her maternal great-aunt and Laguna Pueblo great-uncle – whom she respectfully calls her grandparents.

She received a received a Bachelors in University Studies, from the University of New Mexico, focused on English (Professional Writing and Native American Studies), Linguistics (Native languages) and Native American Studies. As part of the Circle of Learning cohort, she holds a Masters in Library and Information Science from San José State University where she focused on the career pathway of Archives and Records Management. She is also the archivist for the New Mexico Library Association (NMLA) and the 2019-20 chairwoman for the NMLA Native American Libraries – Special Interest Group.