Happy New Year!

January 6, 2021

As we cycle from the Winter Solstice toward the Spring Equinox, we welcome the expanding daylight hours and warming temperatures. In the Pueblos, the year starts with celebration as appointed and elected tribal leaders are announced. Once a governor is chosen or selected, canes are blessed and ceremonially handed to the new governor. On January 6th, King’s Day, most Pueblos would have dances – buffalo, deer, and eagle – open to the public to honor tribal officials.

The office of Pueblo governor was introduced by the Spaniards and is incorporated into the tribal governmental institution. Pueblo governments consist of the Governor, Lt. Governor(s), fiscales, and sheriffs. Some Pueblos like Acoma, Cochiti, and Jemez, officials are appointed by religious leaders. Others, like Isleta, Laguna, or Ohkay Owingeh have an election every two years.

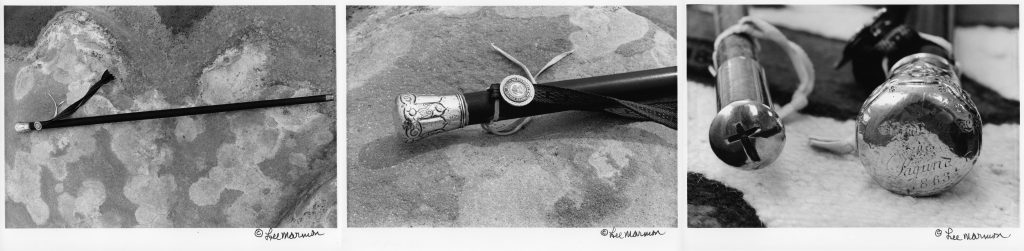

Pueblo Canes

The Governors’ canes are symbols of justice and leadership. There are two canes from Spain. The first came from King Phillip given in about 1620. An engraved cross at the head of the cane indicated the blessing of the Catholic church. The bearer had the support of the Spanish Crown. A second was presented by King Juan Carlos during his visit to New Mexico in September of 1987. When Mexico won independence from Spain, a cane was presented to the Pueblos in 1821, which mirrored the first Spanish cane’s authority.

Associate Producers: Matthew J. Martinez (Ohkay Owingeh)and Conroy Chino (Acoma). Narrated by Wes Studi (Cherokee).

President Lincoln was the first United States President to acknowledge the sovereignty of the nineteen New Mexico Pueblos. Lincoln gave nineteen silver-crowned canes to each of the Pueblos. Each was inscribed with the name of the Pueblo, the year 1863, and “A. Lincoln.”

In 1980, a third cane was presented to the governors by New Mexico Governor Bruce King. On January 7, 1992, a descendant of Christopher Columbus with the same name, gave the Pueblos another cane. Taos Pueblo was given a cane by President Nixon in 1970 when the Blue Lake was returned to the Pueblo.

As referenced in the video included, the canes symbolize the sovereignty of the Pueblo people and the authority of their tribal governments. The nineteen Pueblos are the only tribal nations in the United States to have such a recognition.

At the 2013 Mid-Year Conference, the National Congress of American Indians passed the resolution: Support for the Pueblos of New Mexico Honoring Celebration of 150 Years of the Lincoln Canes.

Tribal Sovereignty

Tribal sovereignty is a tribe’s inherent right to self-govern their people and territory, and to self-determine their futures. From time immemorial, before the arrival of Europeans to this land, tribal nations have been sovereign. Federal permission is not necessary for a tribal government to regulate conduct in their jurisdiction according to their own laws and principles and to adjudicate regulatory disputes in their own forums.

Self-government is essential for tribal communities to continue to protect their unique cultures and identities. Federal support for tribal self-determination and federal-tribal consultation and cooperation allows tribal governments to determine what their priorities are – jobs, education, crime, healthcare, food supply, land and water management, and so on – and how best to meet those needs.

Albuquerque Becomes First City in America to Recognize Tribal Sovereignty by Establishing Government-to-Government Relations

In March 2019, Albuquerque became the first city in America to recognize tribal sovereignty. Here, Mayor Tim Keller, Councilor Ken Sanchez, who sponsored the bill, and Tribal leaders signed the first-of-its-kind bill into law.

“The ordinance recognizes tribal sovereignty and self-determination for tribal governments and requires the City to establish a government-to-government relationship between Albuquerque and the surrounding Pueblos and tribes. It also mandates the board to regularly consult with tribal governments on actions that affect federally recognized tribal governments and to assess the impact of City programs on tribal communities.”

Books

Keeping Promises: What is Sovereignty and Other Questions About Indian Country

Written by Betty Reid (Navajo) and Ben Winton (Pascua Yaqui Aztec, Crow)

Learn how land, ceremony, tradition, history, law, and politics intersect to define tribal sovereignty. Keeping Promises describes the complex but important relationship between Indian tribes and the U.S. government. It describes the relationship between the nations and states, local government, and other tribal governments.

Keeping Promises concisely and simply answers questions about law enforcement, Indian gaming, reservation boundaries, and other subjects. Most important, it helps us understand how Indians define themselves, their tribes, and their sovereignty.

The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book

Written by Gord Hill (Kwakwaka‘wakw)

A powerful and historically accurate graphic portrayal of Indigenous peoples’ resistance to the European colonization of the Americas, beginning with the Spanish invasion under Christopher Columbus and ending with the Six Nations land reclamation in Ontario in 2006.

With strong, plain language and evocative illustrations, The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book documents the fighting spirit and ongoing resistance of Indigenous peoples through five hundred years of genocide, massacres, torture, rape, displacement, and assimilation: a necessary antidote to the conventional history of the Americas. Includes an introduction by activist Ward Churchill, leader of the American Indian Movement in Colorado and a prolific writer on Indigenous resistance issues.

Pueblo Sovereignty: Indian Land and Water in New Mexico and Texas

by Malcolm Ebright and Rick Hendricks

Over five centuries of foreign rule—by Spain, Mexico, and the United States—Native American pueblos have confronted attacks on their sovereignty and encroachments on their land and water rights. How five New Mexico and Texas pueblos did this, in some cases multiple times, forms the history of cultural resilience and tenacity chronicled in Pueblo Sovereignty.

The authors trace the complex tangle of conflicting jurisdictions and laws these pueblos faced when defending their extremely limited land and water resources. The communities often met such challenges in court and, sometimes, as in the case of Tesuque Pueblo in 1922, took matters into their own hands. Ebright and Hendricks describe how—at times aided by appointed Spanish officials, private lawyers, priests, and Indian agents—each pueblo resisted various non-Indian, institutional, and legal pressures; and how each suffered defeat in the Court of Private Land Claims and the Pueblo Lands Board, only to assert its sovereignty again and again.

Their stories, documented here in extraordinary detail, are critical to a complete understanding of the history of the Pueblos and of the American Southwest.

Teaching Resources

IndigNM

Our project aims to provide resources and Indigenous perspectives that will inspire inquiry and debate on the complexity of New Mexico history. We have identified various types of resources that align with a framework to provide counter-narratives in NM History for curriculum, instruction, and policy in high school social studies.

We have created this website to provide easy access to high school social studies educators everywhere. We aim to provide a resource for the public that speaks to the criticality of knowing the history of New Mexico from Indigenous perspectives.

In doing this, our goal is to fill in the gap of perspectives regarding New Mexico’s Indigenous Peoples and how it has evolved and changed over time.

Topics: Cultural Expressions, Identity, Language, Persecution, and Urbanization. Includes resource list.

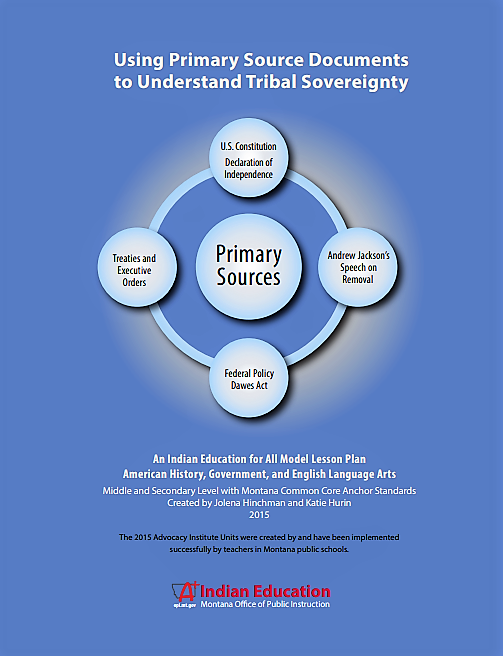

Using Primary Source Documents to Understand Tribal Sovereignty – Montana Office of Public Instruction

An Indian Education for all lesson plan. American History, Government, and English Language Arts. Middle and Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Anchor Standards. Created by JoLena Hinchman and Katie Hurin.

The 2015 Advocacy Institute Units were created by and have been implemented successfully by teachers in Montana public schools.

Fun Stuff

The last in the series has the “Pueblo Cane Story” told by Laura Jagles (Tesuque Pueblo).

Library Shelfie Day – January 27

Created by the New York Public Library in 2014 to celebrate books. Libraries have grown from a place of housing and borrowing books to places of study, storytelling, arts and crafts, computer and printer services, and accessing information online, in databases, and digital libraries.

Open hours for public libraries vary. Some are closed. However, book lovers can still post a selfie of a shelfie to social media of you and your bookshelves. #LibraryShelfie #Shelfie

References

City of Albuquerque. (2019, March 12). Albuquerque becomes first city in America to recognize tribal sovereignty by establishing government-to-government relations. [Press release]. https://www.cabq.gov/mayor/news/albuquerque-becomes-first-city-in-america-to-recognize-tribal-sovereignty-by-establishing-government-to-government-relations

Ebright, M. & Hendricks, R. (2019). Pueblo sovereignty: Indian land and water in New Mexico and Texas. University of Oklahoma Press.

National Congress of American Indians. (n.d.) Tribal governance. https://www.ncai.org/policy-issues/tribal-governance

Native American Financial Services Association. (n.d.) Historical Tribal Sovereignty & Relations. https://nativefinance.org/historical-sovereignty-relations/

Pierce, P.A. & Durrie, N. (2012). Canes of power. Silver Bullet Productions.

Sando, J. S. (1992). Pueblo nations: Eight centuries of Pueblo Indian history. Clear Light.

SantaFe.com. (2020) Treasured Lincoln canes – A living spirit of New Mexico’s tribes. https://santafe.com/treasured-lincoln-canes-a-living-spirit-of-new-mexicos-tribes/

*The term Indigenous is used broadly to include those labeled Native American, American Indian, Alaska Native, Hawaiian, First Nations, Aboriginal, and others like the Sami (Finland) and Ainu (Japan). Native American and American Indian are used interchangeably in this blog.

About the Author

Jonna C. Paden, Librarian and Archivist at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center (IPCC) Library and Archives, is a tribally enrolled member of Acoma Pueblo.

As part of the Circle of Learning cohort, she holds a Masters in Library and Information Science from San José State University where she focused on the career pathway of Archives and Records Management. She is also the archivist for the New Mexico Library Association (NMLA) and previous(2020) and current Chair for the NMLA Native American Libraries – Special Interest Group. (NALSIG)