Indigenous Connections & Collections – Federal Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report

This blog aspires to connect readers to Indigenous* resources, information, and fun stuff at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center (IPCC) and online. Each month, new content will be shared on various themes.

This content is of a sensitive nature and may be disturbing or distressing.

July 2, 2022

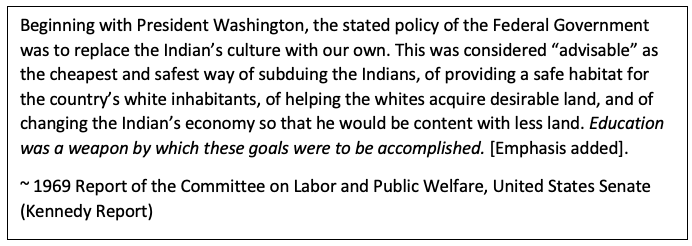

The United States and Canada instituted boarding and residential school systems, respectively, which forcibly assimilated Indigenous peoples into American and Canadian society through the means of education. History shows that cultural assimilation corresponded with land dispossession.

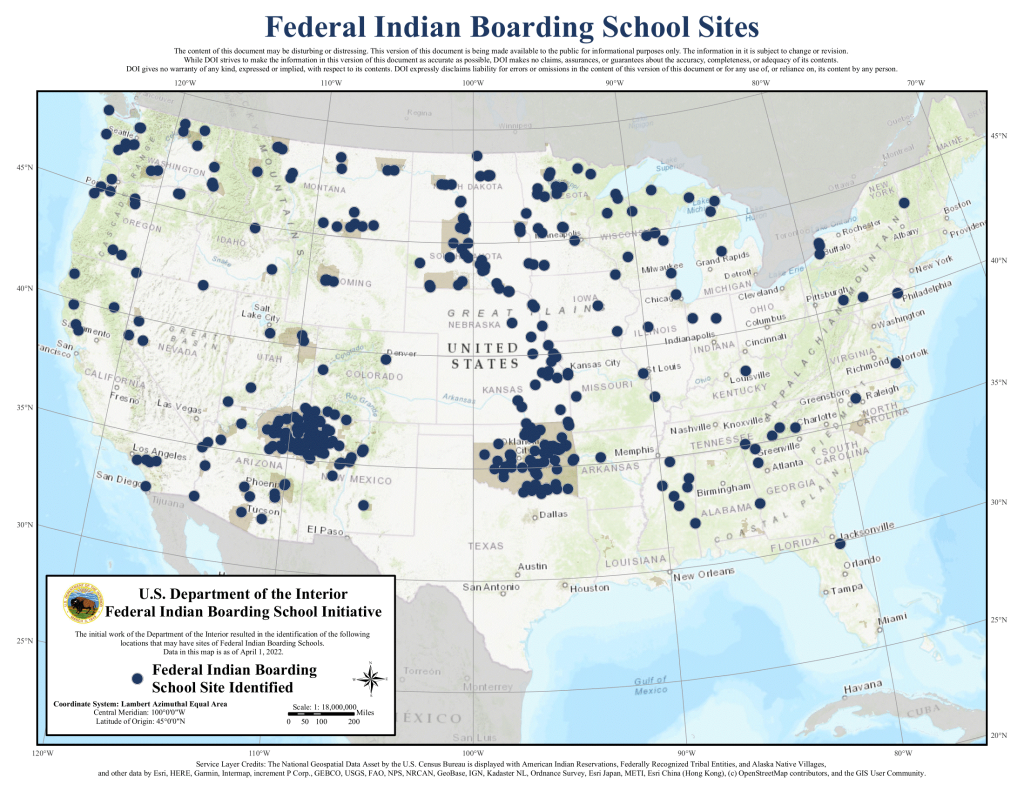

In June 2021, Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, a comprehensive review of the United States boarding school policies with the goal of addressing intergenerational impact and understanding traumas of the past. This official report – the first of its kind – provides historical context, listing of school sites with summary profiles, maps of the general location of schools, identifies marked and unmarked burial sites, and details the historical impact of the boarding school system.

Appendix A: Official List of Federal Indian boarding schools, organized by state (or then territory)

Appendix B: Summaries for each Federal Indian boarding school

NABS: List of U.S. Indian Boarding Schools

Appendix C Federal Indian Borading School Maps (indianz.com)

Indian Boarding Schools

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report shows that between 1819 and 1969, the United States operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states (or then territories), including 21 schools in Alaska, and 7 schools in Hawai’i. There are no exact numbers of Native children – some as young as age three – that were forcibly removed from their families and communities and placed in boarding schools. By 1900, there were at least 20,000 children in schools. By 1925, that number had more than tripled. (NABS)

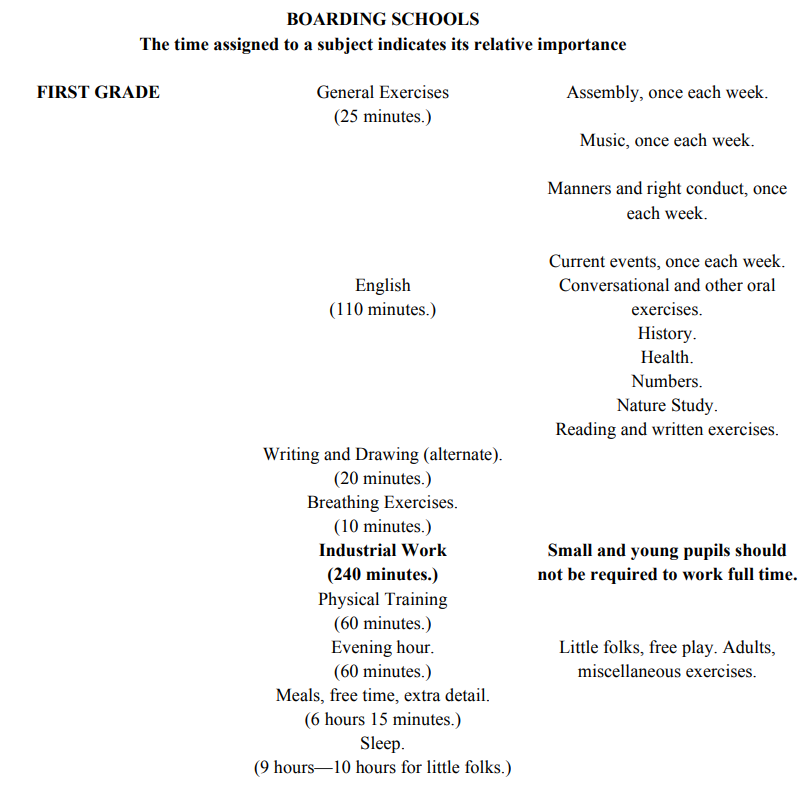

School subjects emphasized European-American beliefs and values. The days were kept to a strict schedule that emphasized the importance of work. Students were forced to convert to Christianity and were not allowed to practice ceremonial customs or speak their tribal language. They were punished if they didn’t speak English. To encourage discipline, students were made to do military drills.

The Federal Indian boarding school system focused on a variety of vocational training, which led to use of child manual labor to help run the schools. Vocational training was seen as more practical than text-book learning. Students were instructed in livestock and poultry care, and agriculture production – including for sales outside the school system. They also learned lumbering, worked on the railroad, dug wells, made furniture, and did laundry, ironing, and garment-making. (Not a complete list.) The Investigate Report states that “the economic contribution of Indian and Native Hawaiian children to the Federal Indian boarding school system and beyond remains unknown.’ (DOI, 2022)

Curriculum for first grade students in 1917. (DOI, 2022)

The Department explained the need for Indian child manual labor as follows:

In our Indian schools a large amount of productive work is necessary. They could not possibly be maintained on the amounts appropriated by Congress for their support were it not for the fact that students are required to do the washing, ironing, baking, cooking, sewing, to care for the dairy, farm, garden grounds, buildings, etc. an amount of the labor that has in the aggregate a very appreciable monetary value. (Meriam Report, 1928)

Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools

KUED takes a moving and insightful look into the history, operation, and legacy of the federal Indian Boarding School system, whose goal was total assimilation of Native American s at the cost of stripping away Native culture, tradition, and language.

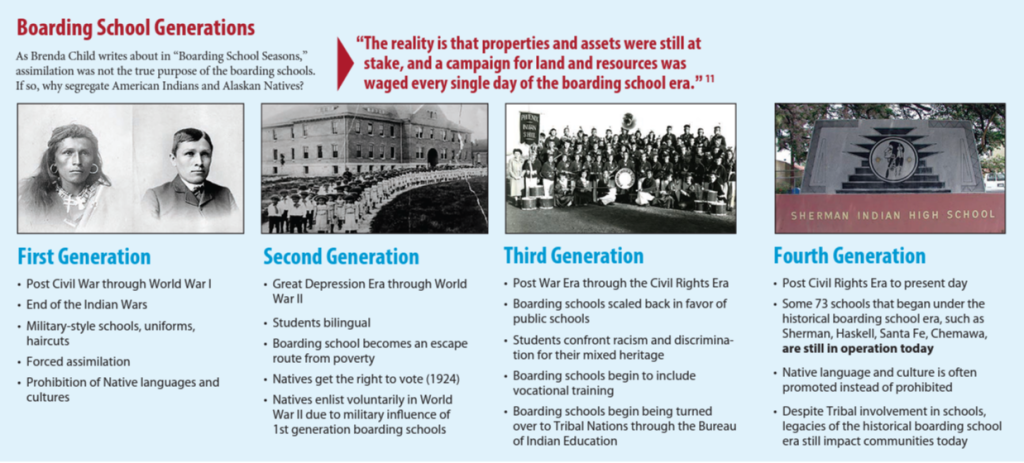

NABS Newsletter: Boarding School Generations

Carlisle Indian School

Brief History of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and CISDRC

The United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, generally known as Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. Richard Henry Pratt, a U.S. Army commissioned officer, secured Carlisle Barracks, a deserted military base, for the site of his school.

Pratt developed a method of Indian assimilation through education when he oversaw Kiowa, Comanche, and Arapaho prisoners of war in a Saint Augustine, Florida jail. The men were taught English, European culture, vocational skills, and dressed in European clothing. Thus begin Pratt’s approach to “civilizing” Native Americans.

Carlisle became the model for other boarding schools. Because Indians were thought to be “good with their hands,” they were taught manual trades rather than educated to be doctors, teachers, or lawyers. Half the day was spent learning reading, writing, and arithmetic. The other half centered on vocational training.

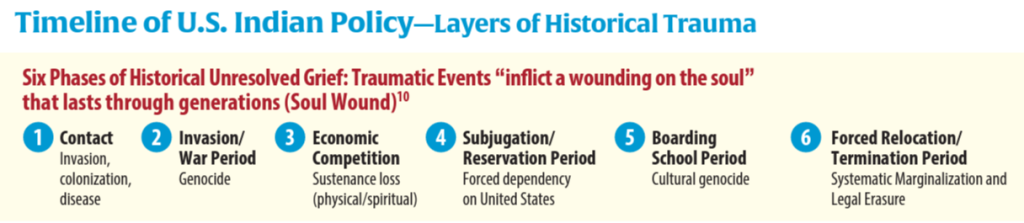

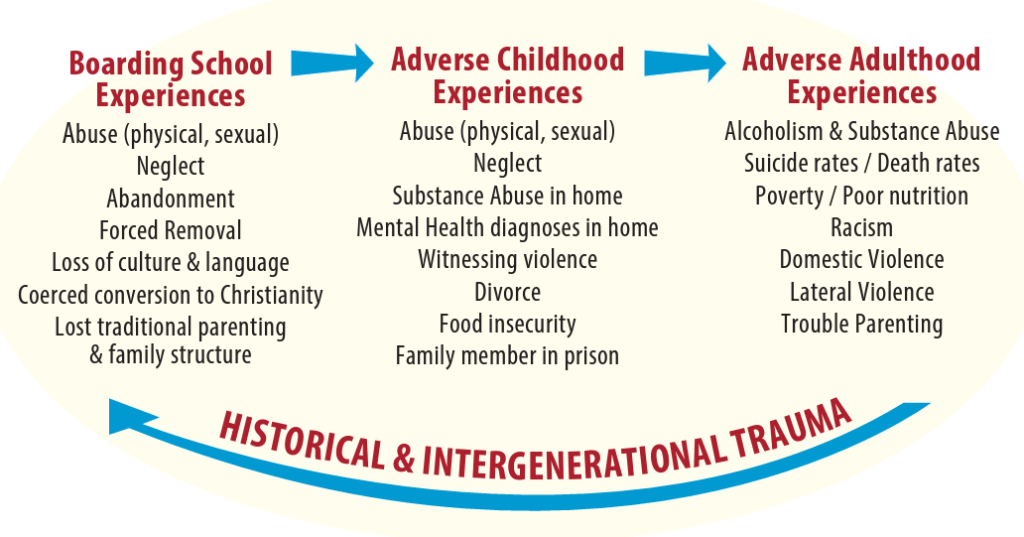

Historical and Intergenerational Trauma

The U.S. federal government’s Indian Boarding School Policy has caused historical trauma and intergenerational trauma on American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN), and Native Hawaiian people. Children were intentionally displaced from their home area and sent to schools far away. For example, Alaskan natives were sent to the Chilocco Boarding School in Oklahoma. In dormitories, children were intentionally mixed in order to disrupt tribal relations and to prevent the use of their tribal language with those of their own tribe.

In taking children from communities, family ties were disrupted, as well as cultural connections to places. In 1803, the Indian Policy meant to dispossess Indian tribes of their territories, partly by assimilation. It was thought that once educated, children would have no need to return to their homelands and, therefore, that land could be acquired “to make room for the cultivators of the earth.” (DOI, 2022)

The Investigative Report states that “systemic identity-alteration methodologies” were employed in Federal Indian boarding schools. This includes renaming from Indian names to English names, cutting of hair, dress in military or other uniforms. (DOI, 2022) Children were punished for speaking Indigenous languages, and practicing cultural customs and spiritual beliefs. They suffered a range of human rights violations – physical, sexual, psychological, emotional, and spiritual abuse and neglect. School rules were enforced using corporeal punishment, such as flogging and whippings, solitary confinement, withholding of food, and other means like balancing the knees on a broomstick with the nose pressed to a wall. At times, older children were made to punish younger children. Some died at the schools and never returned home.

Native American families in Western New York continue to feel the impact of the Thomas Indian School and the Mohawk Institute. Survivors speak of traumatic separation from their families, abuse, and a systematic assault on their language and culture. Western New York Native American communities are presently attempting to heal the wounds and break the cycle inter-generational trauma resulting from the boarding school experience. Unseen Tears documents testimonies of boarding school survivors, their families, and social service providers.

Books

A list of books by Indigenous writers curated by author David A. Robertson (Cree) whose grandmother, Sarah Robertson, attended Norway House Indian Residential School (Manitoba) in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Children’s books curated by Angeline P. Hoffman (White Mountain Apache).

Listing of books from The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

__________

References

Department of the Interior. (2022). Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. https://www.bia.gov/sites/default/files/dup/inline-files/bsi_investigative_report_may_2022_508.pdf

National Indian Law Library. (1969). Indian Education: A National Tragedy – A National Challenge (Kennedy Report). https://narf.org/nill/resources/education/reports/kennedy/toc.html

National Indian Law Library. (1928, February 21). Meriam Report: The Problem of Indian Administration. https://www.narf.org/nill/resources/meriam.html

National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. (2020). Healing Voices Volume 1: A Primer on American Indian and Alaska Native Boarding Schools in the U.S. https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.187/ee8.a33.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/NABS-Newsletter-2020-7-1-spreads.pdf

National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. (n.d.). U.S. Indian Boarding School History. https://boardingschoolhealing.org/education/us-indian-boarding-school-history/

__________

*The term Indigenous is used broadly to include those labeled Native American, American Indian, Alaska Native, Hawaiian, First Nations, Aboriginal, and others such as the Sami (Finland) and Ainu (Japan). Native American and American Indian are used generally and interchangeably in this blog.

About the Author

Jonna C. Paden, Librarian and Archivist, is a tribally enrolled member of Acoma Pueblo. Part of the Circle of Learning cohort, she holds a Masters in Library and Information Science from San José State University where she focused on the career pathway of Archives and Records Management. She is also the Archivist for the New Mexico Library Association (NMLA) and current Chair (2020-2022) for the New Mexico Library Association (NMLA) Native American Libraries – Special Interest Group (NALSIG).