Pueblo Revolt

August 6, 2022

Since time immemorial, our Pueblo history has been filled with resilience and resistance, whether every day subsistence activities of living on our lands or life-changing events that require a larger collaborative community effort, such as the Pueblo Revolts of 1680 and 1696. Through the centuries, we have adapted and stayed strong. Resilience runs through our blood.

This month’s blog revisits and expands on the August 2021 post about the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and the leader, Po’pay.

Monthly Feature: Pueblo Revolt

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 is a regularly inquired about subject. Researchers seek the Pueblo perspective, which is not likely to have been recorded. If it was, those records probably perished in the burning of buildings during the revolt. As Aguilar writes, Pueblo people have their own accounts of the revolt. Some have been shared and some not. “Some Pueblo accounts have been purposely suppressed in the historical memory of communities.” (p. 47) In his book, Pueblo Revolt: The Secret Rebellion that Drove the Spaniards Out of the Southwest, David Roberts presents one reason why, previous to current times, some Pueblo youth did not learn details of the Pueblo Revolt until college. As a life-changing event, that knowledge served no use.

Histories are primarily based on Spanish colonial journals and Franciscan ecclesiastical correspondence and are often biased. As professor, author and researcher, Matthew Liebmann writes, Indigenous rebellions are either successes or failures. “Successful” revolts result in the establishment of liberty or self-rule. Anything less than permanent decolonized independence is considered a failure.

Appraisals of Indigenous resistance tend to be Eurocentric. After a rebellion, the narrative turns toward the assimilation of tribal people and communities into the American mainstream. It rarely documents the after effects of colonization on a people. While the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 is recognized in American history as one of the first Native revolutions, more interesting is what occurred in Pueblo communities in the twelve years before the return of the Spanish. For example, Alfonso Ortiz (Ohkay Owingeh) cites religious restoration, cultural revitalization, population movement and dislocation, and the possible creation of the antecedent to the All Pueblo Council of Governors, formerly the All Indian Pueblo Council. (Aguilar)

The revolt might have shared meaning, but was not a shared experience. (Aguilar) There are a diversity of meanings and experiences based on, among other things, physical location, migrations, settler encounters, and cultural beliefs. What is shared and evident is the struggle, adaption, strength, and resilience of the Pueblo people and communities in the almost five hundred years since first contact with the Spanish.

Monthly Feature: Pueblo Revolt

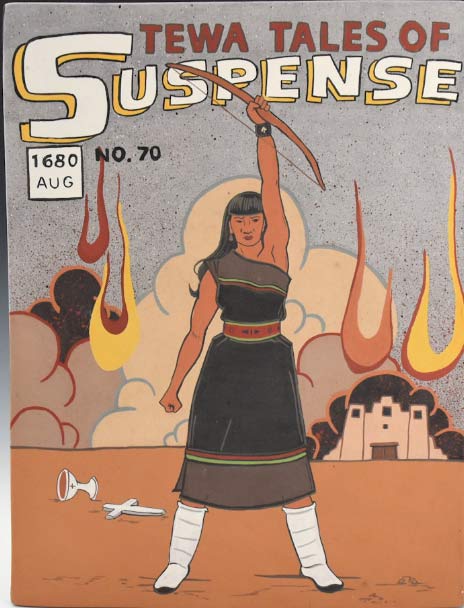

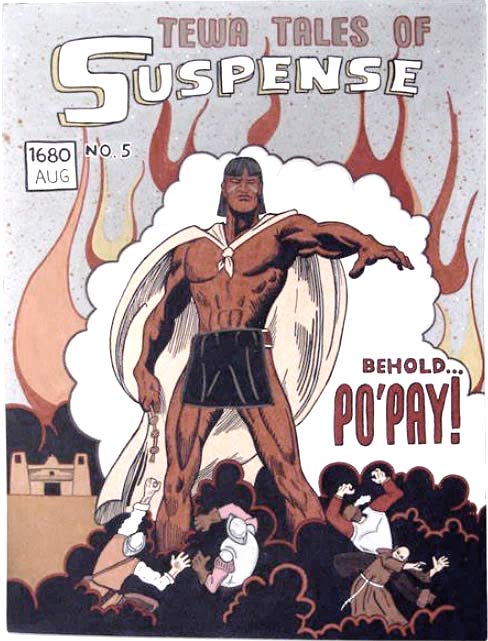

Jason Garcia (Tewa/Santa Clara Pueblo)

Born about 1630, Po’pay (Ohkay Owingeh/San Juan Pueblo) – whose name, Popyn, means Ripe squash in Tewa – was a farmer and part of the medicine society. In 1675, Po’pay and 46 other Pueblo leaders were convicted of sorcery. Those practicing traditional religious practices were tortured and sometimes executed by the Spanish settlers. Po’pay was flogged.

Pueblo leaders had been meeting to discuss how to approach and deal with the Spaniards. They agreed that the Spaniards needed to leave. Po’pay was chosen as leader. August 13 was chosen as the day the Pueblos would begin to force the Spaniards out of the Pueblo homelands. Runners carried knotted cords as they ran to notify the distant Pueblos of the plan. Each day a knot was to be undone. The day of the last knot signified the day of the uprising. Catua and Omtua (Taytsugeh Oweengeh/Tesuque Pueblo) were caught, questioned, and hanged. The revolt started sooner than planned on August 10th.

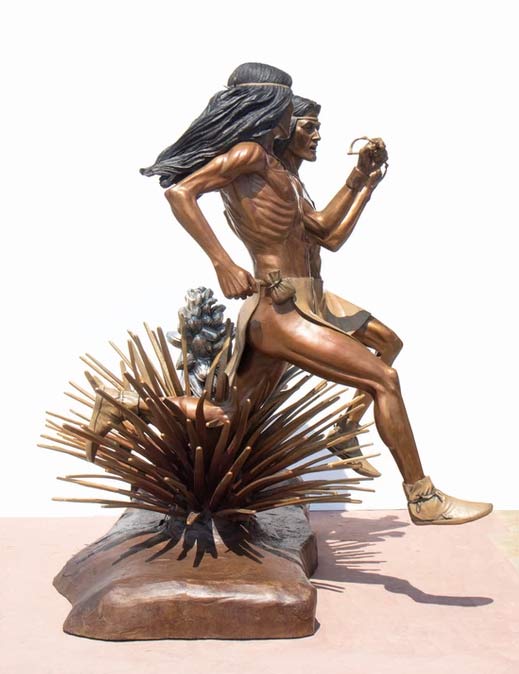

Cliff Fragua (sculptor) describes the sculpture:

In my rendition, he holds in his hands items that will determine the future existence of the Pueblo people. The knotted cord in his left hand was used to determine when the Revolt would begin. As to how many knots were used is debatable, but I feel that it must have taken many days to plan and notify most of the Pueblos. The bear fetish in his right hand symbolizes the center of the Pueblo world, the Pueblo religion. The pot behind him symbolizes the Pueblo culture, and the deerskin he wears is a humble symbol of his status as a provider. The necklace that he wears is a constant reminder of where life began, and his clothing consists of a loin cloth and moccasins in Pueblo fashion. His hair is cut in Pueblo tradition and bound in a chongo. On his back are the scars that remain from the whipping he received for his participation and faith in the Pueblo ceremonies and religion.

Cliff Fragua (Jemez)

Installed in 2005 at the National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, Po’pay, is one of seven statues that honors a Native American and is the only statue carved by a Native American sculptor.

Cliff Fragua (Walatowa–Jemez Pueblo) had no visual reference for Po’pay. The seven-foot statue, carved from pink Tennessee marble, was chosen because its hue “is more closer to our skin color.”

A second Po’pay statue at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center was crafted with a stronger statement – a broken crucifix and a Pueblo drum, which represent traditional Pueblo songs and dances.

Books

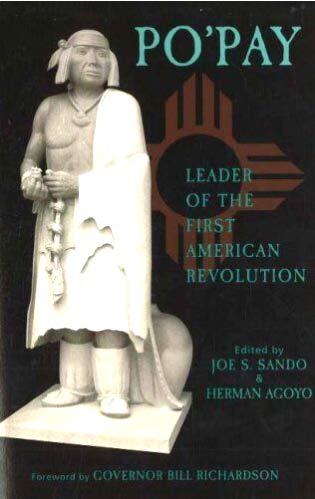

Po’pay: Leader of the First American Revolution chronicles the history of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and its leader, Po’pay, with commentaries on the historical and cultural importance of these events. This is the first time Pueblo historians have written about these events in book form; previous volumes reflected Spanish sources or more distant academic viepoints. Drawing on their oral history and using their own words, the Pueblo writers discuss the history and importance of Po’pay, the illustrious San Juan Pueblo Indian strategist and warrior who was renowned, respected and revered by their people as a visionary leader. Edited by Joe S. Sando (Jemez Pueblo) & Herman Agoyo (San Juan Pueblo), this book includes contributions by Theodore S. Jojola (Isleta Pueblo), Robert Mirabal (Taos Pueblo), Alfonso Ortiz (San Juan Pueblo), Simon J. Ortiz (Acoma Pueblo), and Joseph H. Suina (Cochiti Pueblo).

Po’pay: Leader of the First American Revolution also provides a comprehensive look at a particular time in New Mexico’s history that changed the state forever, making it the richly multi-cultural “Land of Enchantment” that it is. Amplified with quotes from New Mexico and Pueblo leaders, the book also demonstrates how the events of the Pueblo Revolt enabled the Pueblos, unlike other American Indian groups, to continue their languages, traditions and religion on essentially the same lands from ancient times to today and how Po’pay’s legacy continues to inspire all people. The book also covers the historical making of the seven-foot-tall Tennessee marble statue, from the political processes involved to its actual creation, eventual completion and final dedication in the Statuary Hall on September 22, 2005.

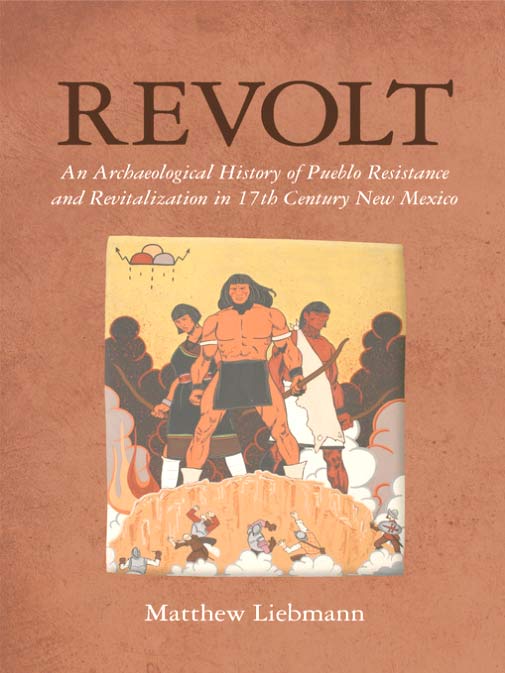

Revolt: An Archaeological History of Pueblo Resistance and Revitalization in 17th Century New Mexico. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 is the most renowned colonial uprisings in the history of the American Southwest. Traditional text-based accounts tend to focus on the revolt and the Spaniards’ reconquest in 1692—completely skipping over the years of indigenous independence that occurred in between. Revolt boldly breaks out of this mold and examines the aftermath of the uprising in colonial New Mexico, focusing on the radical changes it instigated in Pueblo culture and society.

In addition to being the first book-length history of the revolt that incorporates archaeological evidence as a primary source of data, this volume is one of a kind in its attempt to put these events into the larger context of Native American cultural revitalization. Despite the fact that the only surviving records of the revolt were written by Spanish witnesses and contain certain biases, author Matthew Liebmann finds unique ways to bring a fresh perspective to Revolt.

Most notably, he uses his hands-on experience at Ancestral Pueblo archaeological sites—four Pueblo villages constructed between 1680 and 1696 in the Jemez province of New Mexico—to provide an understanding of this period that other treatments have yet to accomplish. By analyzing ceramics, architecture, and rock art of the Pueblo Revolt era, he sheds new light on a period often portrayed as one of unvarying degradation and dissention among Pueblos. A compelling read, Revolt’s “blood-and-thunder” story successfully ties together archaeology, history, and ethnohistory to add a new dimension to this uprising and its aftermath.

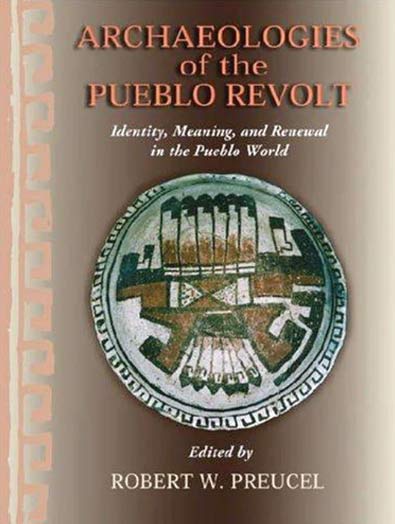

Archaeologies of the Pueblo Revolt: Identity, Meaning, and Renewal in the Pueblo World is the first archaeological investigation of the events and consequences of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The fourteen chapters, written by leading anthropologists and Native scholars including editor Robert W. Preucel and Herman Agoyo of San Juan Pueblo, explore the roles of architecture and settlement in Puebloan society, the uses of ceramics and rock art in belief systems, and the influences of population movements and warfare patterns on social and political organization.

The authors demonstrate that, in the process of resisting Spanish authority, Pueblo people created a new historical consciousness, a collective memory and a mode of interaction which continue to serve them today.

References

Aguilar, J. R. (2019) Asserting sovereignty: An Indigenous archaeology of the Pueblo revolt at Tunyo, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico. (Publication No. 22584386). [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Liebmann, M. (2012). Revolt: An archaeological history of Pueblo resistance and revitalization in 17th century New Mexico. University of Arizona Press.

Roberts, D. (2004). Pueblo revolt: The secret rebellion that drove the Spaniards out of the southwest. Simon & Schuster.

*The term Indigenous is used broadly to include those labeled Native American, American Indian, Alaska Native, Hawaiian, First Nations, Aboriginal, and others such as the Sami (Finland) and Ainu (Japan). Native American and American Indian are used interchangeably in this blog.

About the Author

Jonna C. Paden, Librarian and Archivist, is a tribally enrolled member of Acoma Pueblo. As part of the Circle of Learning cohort, she holds a Masters in Library and Information Science from San José State University where she focused on the career pathway of Archives and Records Management. She is also the archivist for the New Mexico Library Association (NMLA) and previous (2020) and current Chair for the New Mexico Library Association (NMLA) Native American Libraries – Special Interest Group (NALSIG).

Very interesting and informative reading for one of

Tewa decent. It saddens me that the young Pueblo

don’t know their own history. I learned the stories

from my grandfathers, father, mother, uncle and

auntie. Please inform as to how l may purchase the

two books. Kunda- Thank you (Kah-na-wing).