The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center Marks 47th Anniversary ON AUGUST 28, 2022

To commemorate this achievement, we offer an encore of the inspiring story of IPCC, from its founding to the milestones that paved the way to the present day—and lead us into the future.

The Past, Present, and Future of IPCC

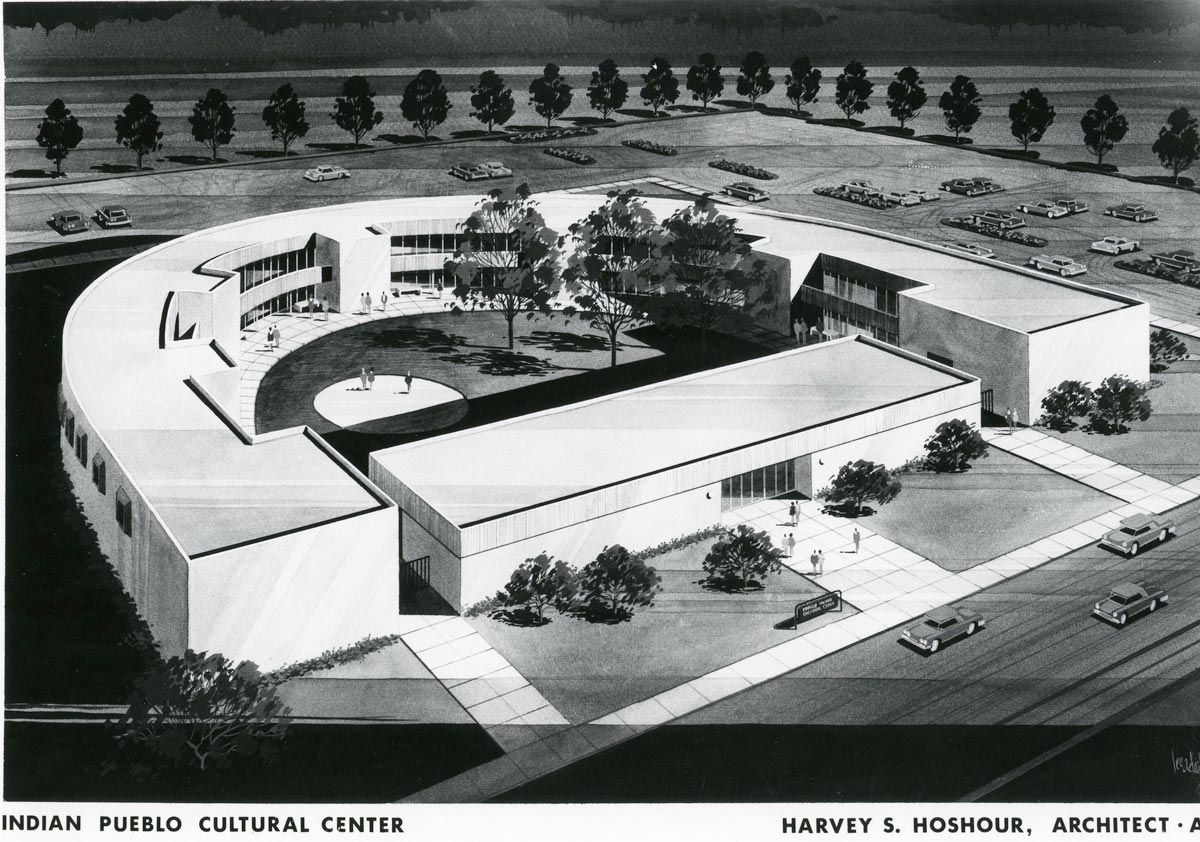

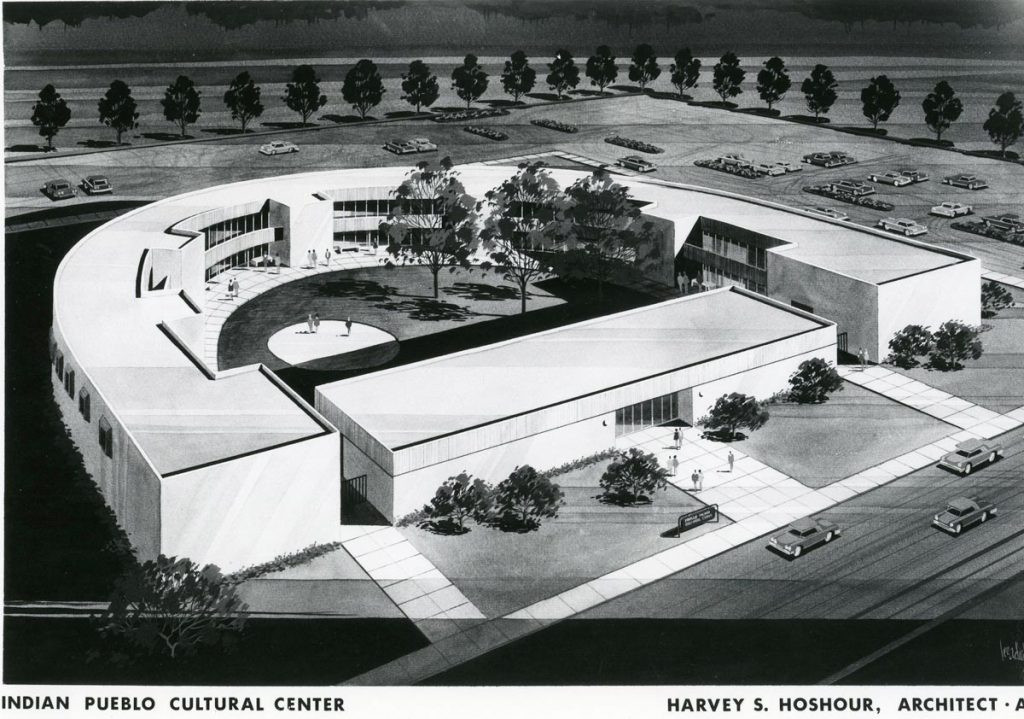

The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center is the inspiring cornerstone of what has grown from a single building into the thriving business and cultural corridor of the 19 Pueblos District in the heart of Albuquerque. IPCC opened its doors in the summer of 1976. The same year the United States was celebrating its 200th birthday, the 19 Pueblos of New Mexico were celebrating something far older—Pueblo culture.

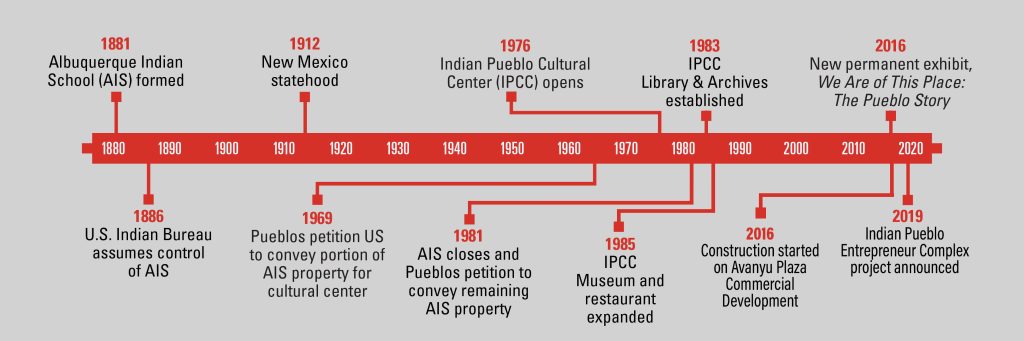

This grand opening of the hub for preserving and perpetuating Pueblo culture was seven years in the making. In 1969, the 19 Pueblos collectively petitioned the federal government to convey a few acres of disused Albuquerque Indian School land to Pueblo ownership for the purpose of establishing a cultural center, and creating economic and cultural opportunities that would benefit tourism and business for the 19 Pueblos, Albuquerque, and New Mexico.

After conducting numerous studies and securing letters of support from city, state, and federal legislators, the endeavor to create the Gateway to the 19 Pueblos was given the green light. Upon opening in 1976, we began curating our permanent collection, which has grown to more than 4,000 objects, and become an invaluable archive for research on Pueblo culture.

As time went on, IPCC’s campus and offerings grew. Our restaurant and museum store opened along with the Center in 1976. The following year, the Friends of the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center—a group of volunteers who raised money from donors around the world—launched the mural campaign that resulted in IPCC becoming home to more than 20 murals by great Pueblo artists. In 1979, we established the Native American Student Art Show to encourage our youth to hone their artistic skills and maintain their cultural connection.

The 1980s ushered in more milestones. When the Albuquerque Indian School closed in 1981, the 19 Pueblos petitioned to have the remaining AIS property across the street from IPCC conveyed to tribal ownership. We established our Library & Archives department in 1983, and 1985 saw expansions of our museum exhibit and restaurant. Throughout the 1990s, the IPCC campus underwent numerous upgrades and remodels, and we celebrated our 20th anniversary.

All of the planning and preparation of the ‘80s and ‘90s led to a boom period in the 2000s. The IPCC is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, but there’s also Indian Pueblos Marketing, Inc., a for-profit enterprise of the 19 Pueblos that generates revenue for Pueblo communities and helps fund some of the cultural and educational programming of IPCC. Between 2004 and 2006, two office buildings were constructed across the street from IPCC, housing the Bureau of Indian Affairs as a long-term tenant.

The 2000s also saw the construction of IPCC’s south entrance, galleries, and ballrooms, as well as the grand east lobby entrance, and expansion of the restaurant. IPMI constructed a Holiday Inn Express across from IPCC, and expanded the old Pueblo Smoke Shop into Four Winds, a large convenience store and gas station that has become an institution for surrounding neighborhoods, as well as travelers.

IPCC and IPMI have accomplished a lot, but this past decade has been particularly invigorating. This period saw the creation of our Indigenous Wisdom curriculum project that provides educators with culturally based, easy-to-follow K–12 lesson plans for each grade level in math, language arts, social studies, and science, plus plenty of hands-on activities.

The annual Pueblo Film Fest debuted in 2014, and in 2015, IPMI opened the largest Starbucks in New Mexico next to the Holiday Inn Express, at what is now Avanyu Plaza. Starbucks at Avanyu Plaza features Pueblo-inspired architecture, and handmade Pueblo pottery and art. Some of the Pueblo artwork commissioned for the Starbucks generated a demand for what became the Pueblo Pottery Mugs, a series of coffee mugs designed by Pueblo artisans. The sale of each mug generates royalties for the artists and Pueblo communities, and makes Pueblo art accessible to people around the world as a portable beacon of culture.

We celebrated our 40th anniversary in 2016 by unveiling our new permanent exhibit, We Are of This Place: the Pueblo Story. It’s an immersive, interactive, multimedia exhibit inspired by traditions that have been passed down for generations, and its displays honor our land and all living things. Not long afterward, we also established the Bob Chavez Scholarship for the Arts, helping Pueblo artists who are pursuing the arts in higher education.

Avanyu Plaza continues to expand in phases with restaurant, retail, and office space development. In Phase I, a Domino’s Pizza and Pueblo-owned Laguna Burger opened as tenants in 2017, followed in 2018 by Sixty-Six Acres, a new dining spot from a popular local restaurateur. A large, decorative, open plaza was completed in 2019, which complements the retail and dining spaces being constructed around it. Across from this new outdoor space, IPMI-owned Marriott TownePlace Suites opened in the summer of 2020. In the spring and summer of 2022, an exciting mix of businesses in Phase II of our commercial development began opening, including US Eagle Federal Credit Union and 12th Street Tavern, a new neighborhood eatery owned and operated by IPMI. Rude Boy Cookies and Itality Plant Based Foods opened in the fall of 2022, and IPMI announced La Montañita Food Co-op, New Mexico’s largest locally owned food co-op, as the anchor tenant for Phase III. In the summer of 2023, Mama’s Minerals and IPMI’s day spa and wellness boutique, Rainwater Wellness, opened their doors. All will continue to draw residents and visitors alike to the thriving 12th Street corridor.

It’s a truly exciting and inspiring time for the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center and Avanyu Plaza. What began as a single building for a museum has flourished into a vibrant cultural and business corridor showcasing the best New Mexico has to offer, all while benefiting city, state, and Pueblo economies.

Today, IPCC is one of the top tourist attractions in New Mexico, and offers plenty of events, dining, and shopping for locals. Over the years our center has grown because of the love, care, and passion of all those who have passed through our doors, growing IPCC into what it is today, and what it will become in the years ahead. Thank you for being part of our story, and being involved in the past, present, and future of IPCC and Pueblo culture!

A Closer Connection to The Pueblo Story Starts Here

Experience a deeper, more meaningful connection to Pueblo people and culture by becoming an IPCC Insider. You’ll have priority access year-round to digital and in-person exhibitions, events, programs and other exclusive offerings.

Join now and start enjoying the benefits of membership. Your support helps us fulfill our mission to preserve and perpetuate Pueblo culture.