International Indigenous Librarians Forum in O’ahu

This blog aspires to connect readers to Indigenous* resources, information, and fun stuff at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center (IPCC) and online. Each month, new content will be shared on various themes.

January 3, 2024

The 2023 International Indigenous Librarians Forum (IILF) was held in at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in Honolulu, O‘ahu. This was my first Forum and my first trip to Hawai‘i. It was wonderful to experience the culture, food, hospitality, and the awe of being on ‘āina (land) surrounded on all sides by wai (water). It was an exciting and inspirational time of learning, finding encouragement and support, and meeting new friends from across the world!

International Indigenous Librarians Forum (IILF)

Te Rōpū Whakahau, the national organization for Māori information workers, hosted the first International Indigenous Librarians Forum (IILF) in November 1999. With the exception of 2021, since the inaugural meeting, the Forum is held every two years. It has been in Australia, Canada, Norway, Sweden, and the United States and is organized by an Indigenous Library Association or by local Indigenous representatives. The IILF is a place for Indigenous information professionals and knowledge keepers — librarians, archivists and museum (LAM) — to discuss goals and challenges, learn about projects, encourage, and celebrate successful efforts and contributions to the lives and futures of their communities. This year’s Forum was held for the first time in Hawai‘i. Among several benefits, a $75,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation helped to increase attendance to the largest ever with about 200 delegates coming from Aotearoa, Australia, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Canada, Norway, the United States and more. The American Indian Library Association had about seventeen librarians and library students from across the U.S. in attendance.

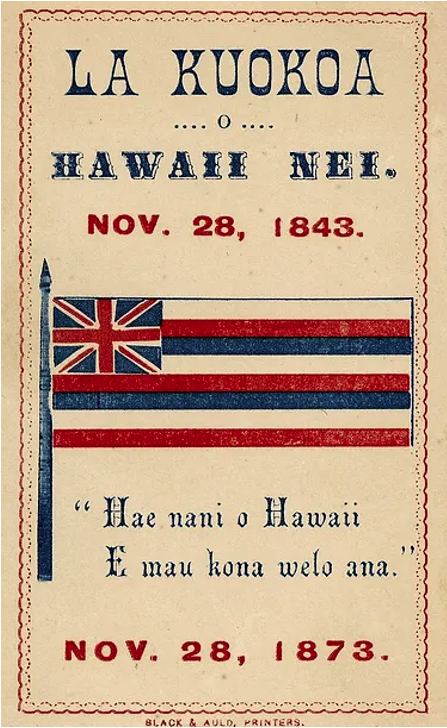

Each IILF has a theme tied to the location and Indigenous people of where the conference is held. This year the IILF dates included November 28, Lā Kū‘ōko‘a (Hawaiian Independence Day). Lā Kū‘ōko‘a served as the kāhua (foundation) of the Forum and was the guide to the theme “Ea: Indigenous Agency and Abundance.” The conference program states: Ea means sovereignty, independence, life, air, breath, and to rise up. Ea as our Forum theme challenges us to think about how we, as Indigenous information professionals, are breathing life into our institutions to advance Indigenous independence and sovereignty within our communities. How are we rising up? How are we lifting up our communities and their fight for ea?”

Day One: Day on the Land

The first day of the Forum is a “Day on the Land” where delegates engage in the local Indigenous land, people, culture, and history through traditional ceremonies, games, cultural demonstrations, and food. This day, we spent at the Waimea Valley on the North Shore of O‘ahu. Delegates were offered guided tours and activities.

Waimea Valley is a wahi kapu (sacred space). “Waimea” means reddish water and refers to the vibrant red soil found here. Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) have lived here as early as 400 A.D. Numerous kahuna (priests) are recorded as having continuously dwelled and ruled from the valley since the eleventh century. Three major heiau (religious places of worship) are located here.

The Day One opening included the welcoming of the mauri stone, an oval rock carved by New Zealand artist, Bernard Makoare, and blessed by Taranaki elder, the late Te Ru Koriri Wharehoka. “The mauri stone was created specifically for IILF, and is imbued with the mauri, or life principle, of the Forum. The mauri stone holds the essence of the discussions, spiritually binding the attendees. At the conclusion of each IILF, the mauri stone is presented to the hosting nation to hold in safekeeping.” [Pamphlet: Day on the Land]

Next followed the delegation presentations of ho‘okupu (offerings) which are more than gestures of gratitude. Ho‘okupu symbolizes “the sharing of knowledge and resources that foster societal well-being by ensuring mutual support across communities and realms.” Delegation ho‘okupu also included cultural songs and dances. The American Indian Library Association offered a beautiful Acoma Pueblo plate. Various individuals also had various ho‘okupu.

Lā Kū‘oko‘a – Independence Day

Day Two: Ka Lā Kū‘oko‘a

Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) celebrate Lā Kū‘ōko‘a as a collective way of honoring their history of power and resilience, of community building, and decolonization rooted in aloha ‘āina (love for the land). 2023 was the 150thanniversary of the Hawaiian National holiday.

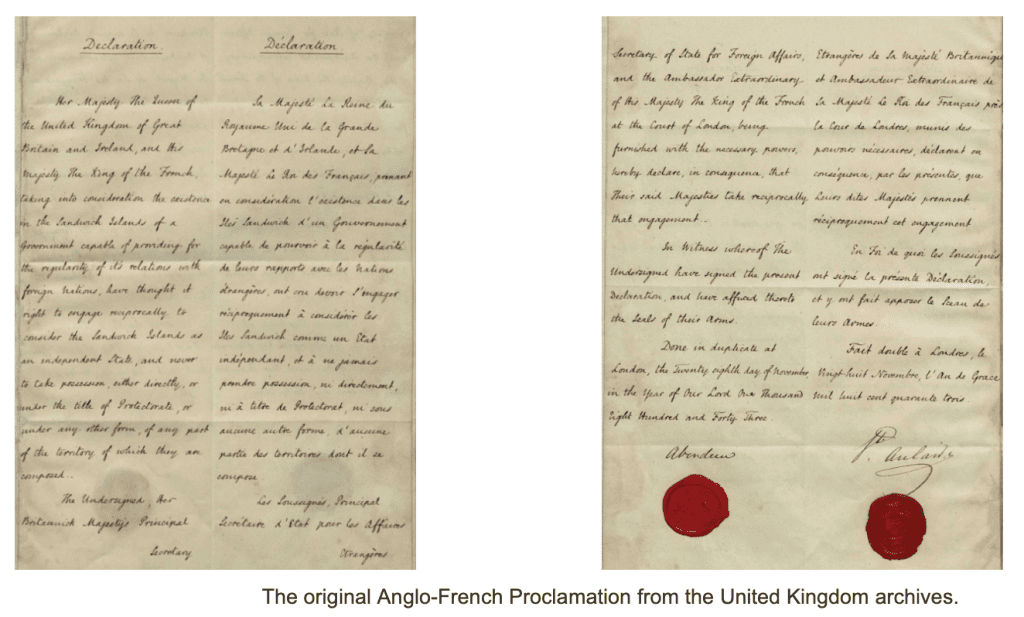

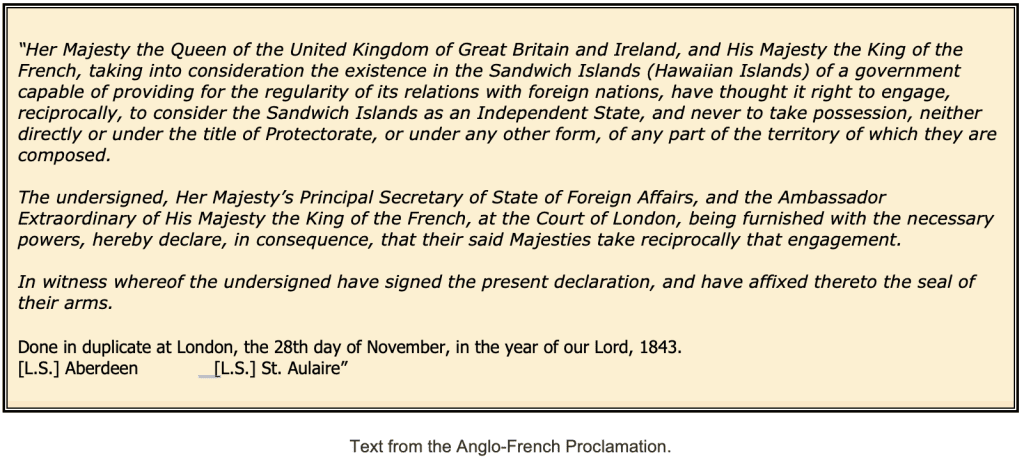

Faced with foreign encroachment, King Kamehameha III (c. 1736-1819) sent a Hawaiian delegation to the United States and to Europe with the power to secure the recognition of Hawaiian Independence. On April 8, 1842, Timoteo Ha‘alilio (c. 1808-1844), William Richards and Sir George Simpson were commissioned as joint ministers with full power to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of their government. Ha‘alilio and Richards traveled to the United States while Simpson went to England.

On December 19, 1842, Ha’alilio and Richards secured assurance from President Tyler of the United States’ recognition of Hawaiian independence. On November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the Britain and French governments formally recognized the independence of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i by signing the Anglo-Franco Proclamation. U.S. Secretary of State John C. Calhoun, on behalf of President Tyler, gave formal recognition of Hawaiian independence. As a result of this recognition, the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into treaties with major nations of the world and established over ninety legation and consulates in various seaports and cities.

In celebration of Lā Kū‘oko‘a, Day Two ended with a pā‘ina, an authentic, traditional Hawaiian feast at Ka Papa Lo‘i ‘o Kānewai on the University campus. Kānewai is a lo‘I, a traditional Hawaiian style of freshwater aquaculture found nowhere else in the world.

The Hawaiian food was catered by Waiahole Poi Factory and included (top to bottom, left to right) lomi salmon, squid lu‘au, chicken long rice, ho‘io salad, haupia (round container), kalua pig, and rice. Yummy with a seafood twist!

Luau brings to mind a Hawaiian feast along with dancing. Tiki drinks, plastic lei, and grass shirts are inaccurate and misinformed Western cultural appropriations. Before the mid-19th century American influence, lū‘au had a traditionally different meaning. Chicken baked in coconut milk with karo was typically the main dish of the feast. The correct Hawaiian word for feast is pā‘ina or ‘aha‘aina.

A quick lession on Hawaiian Foods 101 by Waiahole Poi Factory.

Kanikapila

Day Three: E kanikapila kākou

That evening, IILF delegates were invited to a kanikapila, an informal gathering where music is shared by participants to encourage fun and relationship building. Kanikapila is a combination of the Hawaiian words “kani ka pila” which literally means “the instrument that makes sound.” A common Hawaiian custom, families gathered to sing songs together, usually accompanied by instruments such as the ukelele and ki hō‘alu (Hawaiian slack key guitar). These community gatherings were a relaxed time for people to see and catch up with loved ones, eat some delicious food, and relish the shared joy of music making.

We enjoyed heavy pūpū (appetizers), visited, enjoyed listened to music and singing. I loved hearing the Aotearoa and Hawaiian songs in their language and envied the grace of their gestures along with the various dancers who swayed elegantly across the floor.

Bridging Knowledge Scholarship Program

Day Four: Poster Sessions and Closing

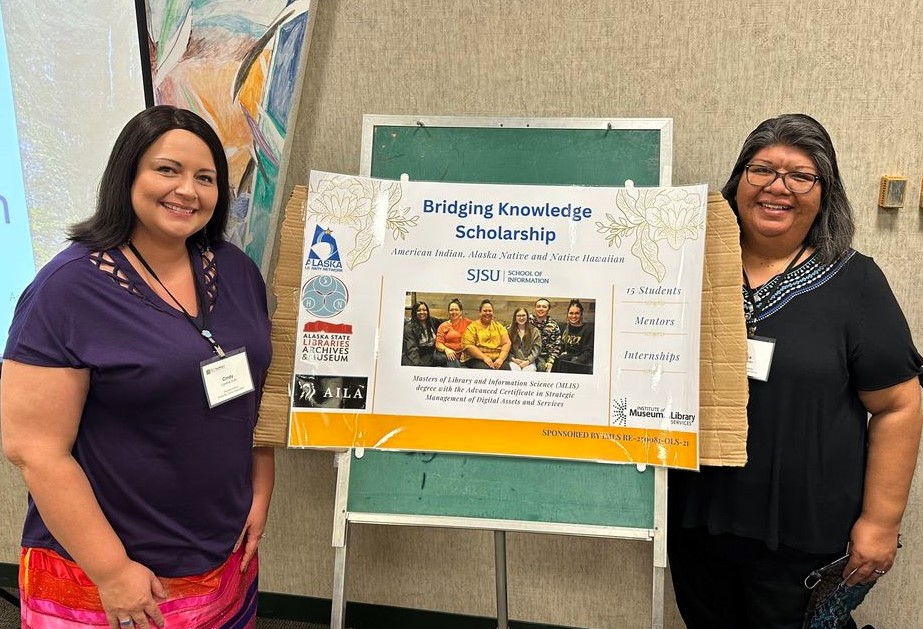

On this last day, delegates visited poster presentations by librarians, professors, information professionals, and students on various topics. Along with Cindy Hohl (Project Manager), I shared information about the Bridging Knowledge online MLIS Program at San Jose State University. This collaboration between the American Indian Library Association, Alaska Library Network, Alask State Libraries, Archives and Museums, and the Sustainable Heritage Network and sponsored by the Institute of Museum and Library Services was created to recruit, build, and support a network of Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Native American students. Our poster was under the subtheme pilina, cultivating Indigenous spaces and networks.

In the afternoon, the Indigenous delegates gathered to enjoy a relaxing time in camaraderie doing various activities like coloring, drawing, discussions as we reflected on various themes, chatted, and learned from one another. We were given time to talk freely about any issues we face and offer advice and support. The non-Indigenous delegates also gathered and discussed ways to be effective allies for Indigenous colleagues and their work.

Mānoa, Hawai‘i

Mānoa is located in the Kona (southern) district of O‘ahu. Its name means “vast” or “wide” and refers to the extensive size of the verdant valley that it comprises. Mānoa is an agriculturally-rich valley due to the well-watered upper valleys, fertile soil and cooler weather. Traditionally, it was home to an extensive lo‘i kalo (wetland taro cultivation) system that produced tons of food annually. King Kamehameha I cultivated ‘uala (sweet potato) here when conquering O‘ahu. Mānoa is known as the favorite home of the ali‘i (royal ones).

Mānoa is home to the University of Hawaii and serves as an integral part of the reclamation and rediscovery of ancestral Hawaiian practices due to the critical research conducted at the Hawai‘inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge. Established in 2007, the School encompasses the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies, Kawaihuelani Center for Hawaiian Language, Ka Papa Lo‘i O Kānewai Cultural Garden and Native Hawaiian Student Services. Hawai‘inuiākea is the only college of Indigenous knowledge in a Research I institution in the United States.

Kamakakūokalani means “upright eye of heaven”; it serves as a metaphor for the Hawaiian Studies program’s higher mission of seeking truth and knowledge. The Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies (KCHS) was named for Gladys Kamakakūokalani ‘Ainoa Brandt, a prominent Native Hawaiian educator who believed it was through education that the Hawaiian people would become more effective agents in carrying out traditional ancestral practices, customs and in transforming, shaping and contributing to the world. The school, its faculty, classes and programs represent Hawaiian perspectives and knowledge within the larger academy. Most courses offered are distinctive and taught nowhere else in the world. (This section and image from the Lā Kū‘ōko‘a Celebration pamphlet.)

Ka Papa Lo‘i ‘o Kānewai Cultural Garden

Existing nowhere else, the lo‘i kalo is an integral part of the Hawaiian cultural ecosystem. It is a traditional wetland garden consisting of planting patches fed by ‘auwai, a complex irrigation system used to raise kalo (taro; Colocasia esculenta) and other crops and animals. Kalo is considered a family member, the elder brother of the Hawaiian people. It is a staple food and is used in medicine and in ceremony.

Ka Papa Lo‘i ‘o Kānewai is an ancestral lo‘i that was discovered on the grounds of the University of Hawaii at Mānoa in the 1980s. It is estimated to be well over 400 years old. It has been revitalized by community members and students and now serves as a pu‘uhonua (place of refuge) for learning Hawaiian knowledge.

References

The Hawaiian Kingdom. (n.d.) International Treaties. https://www.hawaiiankingdom.org/treaties.shtml

Manoa Heritage Center. (n.d.) Kalo (Taro) https://www.manoaheritagecenter.org/moolelo/polynesian-introduction-plants/kalo-taro/

12th International Indigenous Librarians Forum. (2023) Day on the Land: Lā Waimea Welcome Packet. [Pamphlet].

12th International Indigenous Librarians Forum. (2023) Lā Kū‘ōko‘a Celebration [Pamphlet].

About the AuthorJonna C. Paden, IPCC Archivist and Librarian, is a tribally enrolled member of Acoma Pueblo. A member of the Circle of Learning cohort, she holds a Masters in Library and Information Science from San José State University where she focused on the career pathway of Archives and Records Management. She is the Vice-Present/President-elect of the American Indian Library Association, Archivist for the New Mexico Library Association (NMLA) and past Chair (2020-2023) of the New Mexico Library Association (NMLA) Native American Libraries – Special Interest Group (NALSIG).