Unpacking reLocated

One of our current rotating exhibits, “reLocated: Urban Migration, Perseverance, and Adaptation,” is an in-depth multimedia, multisensory presentation on a topic that had a huge impact on Pueblo communities, and much of Native America in general. This special exhibit is a collaborative effort between IPCC’s curatorial team and guest curator Dr. Christina M. Castro (Taos and Jemez Pueblos).

The 1930s brought a huge shift in federal policy toward Native Americans. The 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, or the Indian New Deal, provided funding for education and training of Native people to be competitive in the workforce and earn a living wage. It replaced previous policies that had served to weaken tribal sovereignty. For our Pueblo people, and many Native people across the country, this opportunity for education would almost always require us to leave the reservations and tribal communities for work through an emerging program known as “Relocation” or “Employment Assistance.”

To assimilate our people into mainstream American society, the federal government and many religious organizations operated boarding schools. These schools were places where our children were torn from their homes and forced to abandon their language and culture in favor of English and Western values. By 1925, there were 60,889 children placed in these boarding schools.

Once graduated from these boarding schools, young Native adults often experienced the feeling of not belonging in their home communities due to having been gone so long. Being Native American, they often experienced discrimination in mainstream America. Having been removed from their communities and forced to forget their traditions as youth, they lacked a strong connection to their homes. Because of this, many young men were easily recruited into the military and sent off to war, while others signed up for employment assistance programs.

The need for a growing labor force following WWII led Native Americans into a new era of “urbanization.” Many of our Pueblo people left their homelands for the first time to seek work, and many veterans returning home became frustrated with the limited employment opportunities near home. Some felt no other option than to migrate to urban areas.

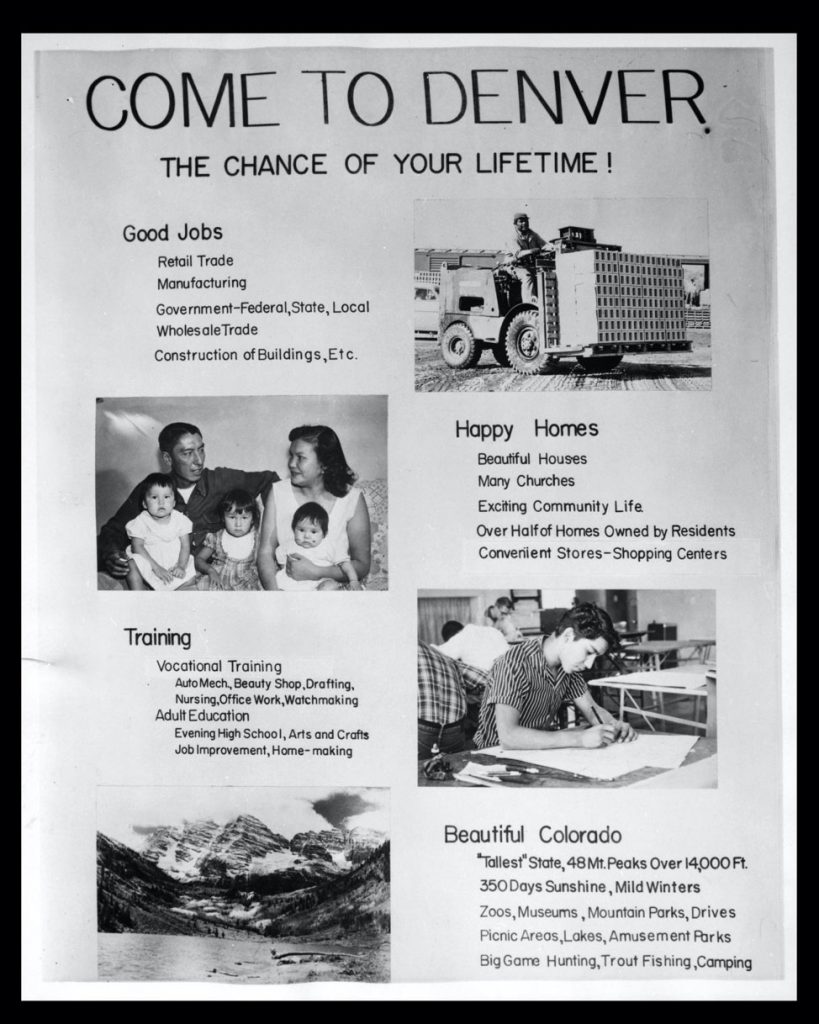

Brochures and pamphlets were distributed throughout the pueblos by Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) officials spinning exciting stories of city life. After an initial inquiry about Relocation at a BIA office, or a conversation with a BIA agent, an appointment would be set to review the applicant’s job skills and employment record. Once selected, the BIA official would contact the relocation office in the city of the applicant’s choice.

Depending on the distance, travel to the city would occur by train or bus. Upon arrival to their destination, they were met by a relocation representative who took them to their housing accommodations, usually a low-income apartment in a poor neighborhood. As part of their initial adjustment, relocation officers would often assist the new arrivals with all aspects of adjusting to city life, including where to shop, identifying local schools their children could attend, and also connecting them with nearby churches. Some relocatees were provided with job skills training. In most cases, after the first month, relocatees were on their own.

While some relocatees chose to return home after several years—even decades—of working in cities, there are many who decided to stay and establish lives there. Families grew roots, and now you see third- and fourth-generation descendants of relocatees living and thriving in urban areas. Many Native Americans in cities are members of middle-class America, holding professional positions and college degrees. There are Native lawyers, scholars, engineers, and doctors. With the added mobility of our times, descendants of our pueblos are able to stay connected to their tribal communities, if they have the means and desire.

Pueblo people who live in cities continue to return “home” for holidays, feast days, and other doings. As Pueblo people, we will continue to migrate and adapt to fit our respective needs because it is something we have always done when necessity calls for such measures.

The relocation program is looked back on with mixed feelings. The U.S. government, along with some of the relocated Native populations, maintain that the program was a success. Others feel the program was only successful in disconnecting individuals from their communities and traditions, creating a subgroup that belonged to both worlds, yet to neither.

Do you have a personal or family story about relocation? We’d love to hear from you. Share it on social media with the hashtag #PuebloRelocated, and it may become part of the digital portion of the exhibit. You can learn even more about the Relocation program, plus experience the full multisensory exhibit running into 2021, by visiting IPCC once it reopens.

If you’d like to help support exhibits like this one, please consider making a donation. Every contribution helps us continue our mission to preserve and perpetuate Pueblo culture, and to provide informative, educational, and entertaining programming for you and people from all around the world.

This is a very interesting part of Pueblo people i did not know. I will be re-reading this over a few times since there is so much information in this post. I enjoy getting this e mail and hope to visit the Center again at some time